Aloisia Moser an der Koc University, Türkei.

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Vienna in the early 90’s I met Zeynep and Leyla in one of my philosophy classes. They were studying philosophy and politics after they went to school in Istanbul at the St. Georg’s Kolleg, where they had learned to speak German fluently as well as all about Austrian culture, including singing folk songs in the dialect. Through meeting them I also came in contact with their culture, a secularized Muslim Turkish identity of the Orhan Pamuk kind that I found absolutely irresistible. After nights of going out with them and staying over at their shared apartment I found out that not only did I like drinking Rakı but also eating olives and feta cheese for breakfast. We were discussing and had different opinions about the PKK, Turkey and a new Europe that would only be founded within the next year. My—or our—dreams from back then have unfortunately not come true. Turkey—after a huge wave of secularization initiated by Atatürk, who was also impressively feminist—has now receded into a divisive and poisonous religious fundamentalism that neither of us could have imagined.

On March 18th I arrived in an Istanbul where neither of my friends live now (they live in Vienna and Minnesota respectively) and in a political situation that has to remind one of the Biedermeier, Istanbul being now a city and society in which people are pulling away from politics and the public sphere into the privacy of their homes. That said, Istanbul is a lively place, more so than Vienna or New York, and I still do not think it to be dangerous. It is easy, especially as a Westerner, to avoid confrontation (which Turkish activists, brave people who are thoroughly political and whom I greatly admire, do not). One knows where one risks running into tear gas. This is not to say that there are not people who are and have been taken away and find themselves in prison on very dubious charges or no charges at all. The politically outspoken live in constant fear and danger. There is a lot of depression among them and society as whole. Turkish media companies have been bought up by business conglomerates without any journalistic expertise but close links to the ruling AKP and the government.

While in Istanbul I also met Jörg Winter, the Middle East correspondent for the ORF (we went to high school together) and who told me that the space of reporting, not only for Turkish but lately also for foreign journalists, has been shrinking. Foreign media are clearly not welcome anymore in Turkey, he says, as the government has started to put more and more pressure on correspondents and their local Turkish employees.

For most, however, all of this can be avoided. Life in Istanbul goes on. Just with far fewer people from the rest of the world.

On my last morning, on the way to the Cemberlitas Hamam, I met a man in the tramway who told me, in perfect German, that for a few years now the Grand Bazaar is lacking buyers from abroad. This man also spoke Greek, Turkish, English, Italian, French, Japanese, in short all the languages he needed to haggle with the customers and which he had learned from spending time with people from all over the world. The sun was shining as our shared tram was gliding by the Hagia Sophia and the Sultan Ahmed Mosque. The man gave me his card upon disembarking at his stop and encouraged me to visit him in the Grand Bazaar on my next visit. I said I would, and then he disappeared from our shared moment of being world citizens, moments of which I had quite a few. For example, I was talking to the son of the owner of my Airbnb situated about 15 minutes from Taksim, in the infamous neighborhood of Tarlabasi that is just now gentrifying. I stayed in a beautifully styled apartment right next to a building that still houses the local chapter of the pro-Kurdish HDP, a party that has come under enormous attack from the government, its leaders imprisoned, and elected officials expelled for their alleged linkes to the PKK. The party has denied these allegations. He told me he had been a student of politics but was now helping in the family business. He grew up in Istanbul, his mother British, his father Turkish. And yes, he had friends who are students at Koç University, and he would alert them so they could come to my talks.

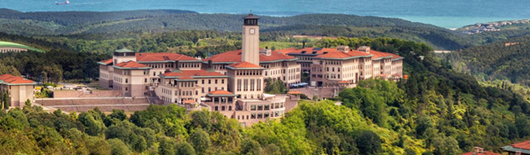

Koç University is a private university situated up north on the Bosporus. I knew it already, since I had applied for a job there five years ago, when I was still in the US, and had been flown in for an on-campus interview. The campus is beautifully situated amid the mountains. The buildings are made of stone, well built, a big university with a lot of style and energy. There are so many cafes around the campus that sometimes one thinks that all the thinking may be done in the cafeteria. The philosophy department is located in the social science building and I quickly found my way around the offices, the seminar and lecture rooms, the aisles with the posters of invited speakers, such as myself.

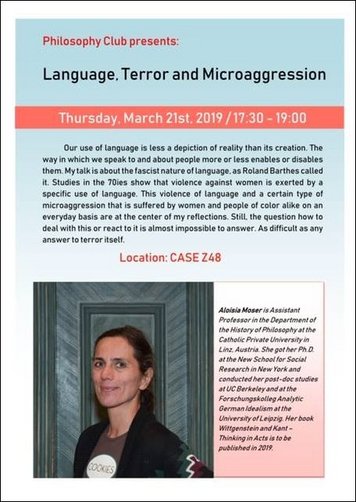

Over the course of my visit I met with all of the philosophy faculty, half of whom are not from Turkey. Zeynep Direk, the chair of the philosophy department, is, but got her degree in the US (as I did). At Koç University all classes are taught in English and the faculty is often from the US or graduated from the Ivy League universities there. I gave my first Erasmus talk in the philosophy colloquium and a second one in the student club. Both talks were followed by discussion engendered by great questions asked by students and faculty alike. My second talk was about language, micro-aggression and terror, and I could not but turn to the situation in Istanbul today. It is difficult to talk about politics in Turkey, since one never knows whether someone is in the room to report. The strategy of the professors is to refer to webpages that the students can go look at instead of saying things directly themselves. Life, student life, university life goes on. I wanted to build the Erasmus bridge, the connection to our university, as I think it is important to strengthen exchange, to be there when things get worse as well as when the tide changes again. I also visited Kültür University near Atatürk Airport to give the same talk on language, terror and micro-aggression in their English Literature department. At the university there seems to be a fear about starting a Cultural Studies program, which the faculty try to overcome–a fear that it may lead to such “dangerous” fields as Kurdish culture and Gülenist studies. Similarly, Women’s and Gender Studies programs are heavily discouraged and discontinued, for the terrifying reason that a different image of woman is wanted. Turkish academics who have decided to stay despite the difficult political situation are committed to their careers, students and to international academia and hoping that people will not refrain from coming but visit to show their support. They have decided to stay and cannot do it alone.

What struck me most in the days in Istanbul was seeing the new mosque being built on Taksim Square. It takes up an immense amount of space, physical and symbolic, and does so on purpose. It has been pulled up in no time, concrete pillars, a spitting image of the big old mosques, but a new, mocking image made from concrete in the year of 2019. It is hard for me to describe how much this image pained me during my stay. I kept thinking about what ugly skyscraper one could have built there, what other symbol: but no, a huge 21st century concrete mosque is being built in the center of Istanbul to make a point. It is not hard to figure out exactly what is the point, as we watch a fundamentalist conservative regime closing in. It is also a fight for public space, which the ruling AKP seems to be winning.

Many colleagues and friends asked me whether I thought it was a good idea to travel to Istanbul now at all. The same happened when I went two years ago to visit my friend Mariana Vassileva, an artist who lives in Germany but has Bulgarian/Turkish roots, who was an artist in residence there for six months. During her stay she created a piece of art, which is simply a microphone with a grenade at the top. I have thought about this piece and the situation in which you cannot speak for fear of the explosion you would create, one that would certainly also hit you, and the decision to retreat into the private sphere. I decided back then not to let Istanbul be taken away from me, and to continue visiting despite having signed the first petition of intellectuals, a list which has been used systematically to take away and imprison intellectuals.

We live in a strange reality concocted by images. Images of mosques being erected in main squares and of Muslims being massacred in them on the other side of the world. All the images are being used in different ways by different people(s). My second talk in the philosophy student club was about that. About how there was no neutral way of using language or images. How language was always already fascist and, as Roland Barthes also says of writing, of how everyone’s individual use of language is terroristic for the very same reason. Barthes also suggested we look for a neutral way, for a grey zone, for a way of talking to each other that does not paint any image black or white. This is what I hope the Erasmus exchange program between our universities will achieve: students going back and forth, building a bridge, keeping the symbols and images in flux.

Aloisia Moser konnte während ihres Aufenthalts in die Forschungstätigkeiten der Philosophischen Fakultät hineinschnuppern sowie zwei Vorträge halten. Das Publikum bestand dabei sowohl aus Studierenden als auch aus Universitätsmitgliedern.

Erasmus: Istanbul 18.-22. März 2019 / Erfahrungsbericht von Aloisia Moser

28.3.2019/he